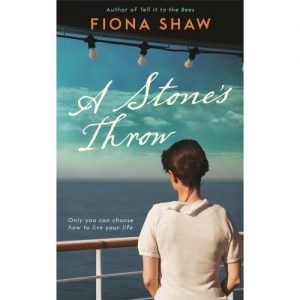

A Stone’s Throw

‘The people you love, they just slip away… I won’t let you do that…’

‘The people you love, they just slip away… I won’t let you do that…’

A man and his young son set out on a journey one snow-struck day. Another man skims stones across the sea with his daughter. Three generations separate them, but one loss connects them – sixty years apart, but no more than a stone’s throw.

In between these two men is Meg. Like everyone, she’s made choices in her life; and mostly she’s proud of them. But that doesn’t mean she isn’t haunted by what might have been . . .

Set in England and Africa, opening during World War Two, A Stone’s Throw is about how secrets linger and the price we pay to keep them. Most of all, it’s about the choices we make, about consequences – and how we must, finally, let go of the past and face the future.

Serpent’s Tail, 2012

Buy A Stone’s Throw from Amazon

Reviews

‘This subtle, poignant, multi-layered family saga presents a haunting exploration of familial and sexual love, duty and self-determination in which the quality of the writing, both elusive and allusive, makes for a profoundly moving and satisfying read.’

Polari Magazine, March 2012

‘I found it totally engrossing, [Fiona Shaw’s] best yet… such a clean style and an honest heart.’

Emma Donoghue

‘A single traumatic event lies at the heart of this exquisitely written novel spanning 60 years, three generations and two continents. Beyond this, however, and central to Meg’s life, are the paths she chose to go down – and those she avoided.’

Henry Sutton, Daily Mirror

‘Fiona Shaw’s affecting novel opens in the midst of the second world war. Travelling by ship to Africa to meet her buttoned-up fiancé, Meg Bryan has an affair with a handsome soldier, but their dalliance is interrupted when German U-boats torpedo the convoy.

Rescued from the wreckage, Meg begins her new life as a colonial housewife in Kenya. As the years pass, she is unable to forget the romance and trauma of the voyage.

Shaw describes her characters as “tiny figures caught between land and sea”; they are buffeted by circumstance and bound by a certain kind of middle-class reticence.

Though she names her chapters “Ice”, “Air”, “Water”, “Fire” and “Earth”, her prose eschews the elemental; it is as subtle and delicate as gossamer.

The description of the sinking ship is a masterclass in restraint: “People jumped and scrambled and tumbled into the sea, and some came up and swam and some never did; and some got away and most didn’t.”’

David Evans, FT, April14, 2012